7 Middle America

Introduction

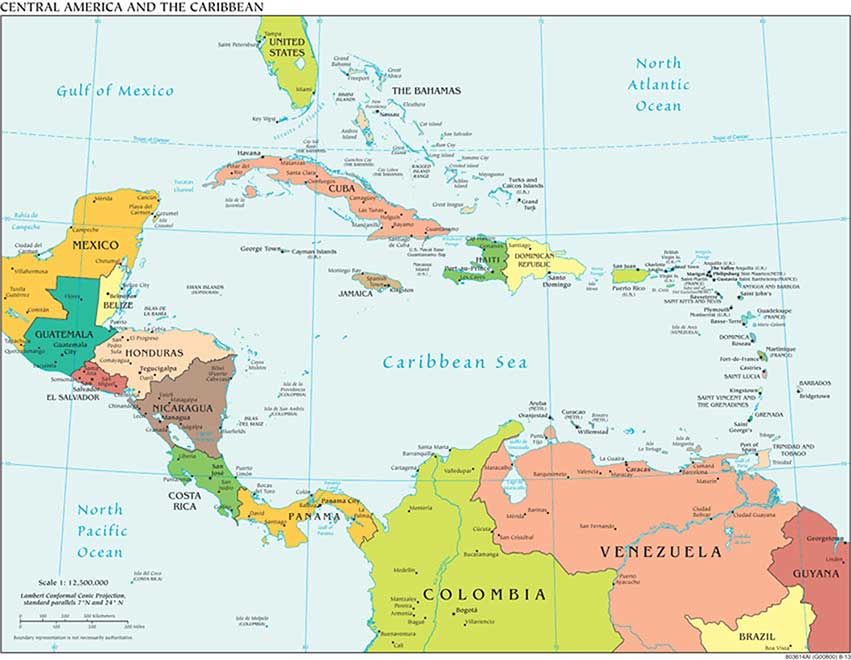

Middle America, the geographic realm between the United States and the continent of South America, consists of three main regions: the Caribbean, Mexico, and the Central American republics. The Caribbean region, the most culturally diverse of the three, consists of more than seven thousand islands that stretch from the Bahamas to Barbados. The four largest islands of the Caribbean make up the Greater Antilles, which include Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico. Hispaniola is split between Haiti in the west and the Dominican Republic in the east. The smaller islands, extending all the way to South America, make up the Lesser Antilles. The island that is farthest south is Trinidad, just off the coast of Venezuela. The Bahamas, the closest islands to the US mainland, are located in the Atlantic Ocean but are associated with the Caribbean region. The Caribbean region is surrounded by bodies of salt water: the Caribbean Sea in the center, the Gulf of Mexico to the west, and the North Atlantic to the east.

Central America refers to the seven states south of Mexico: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. Panama borders the South American country of Colombia. During the colonial era, Panama was included in the part of South America controlled by the Spanish. The Pacific Ocean borders Central America to the west, and the Caribbean Sea borders these countries to the east. While most of the republics have both a Caribbean and a Pacific coastline, Belize has only a Caribbean coast, and El Salvador has only a Pacific coast.

Mexico, the largest country in Middle America, is often studied separately from the Caribbean or Central America. Mexico has an extensive land border with the United States, its neighbor to the north. The Baja Peninsula, the first of Mexico’s two noted peninsulas, borders California and the Pacific Ocean and extends southward from California for 775 miles. The Baja region is mainly a sparsely populated desert area. The Yucatán Peninsula borders Guatemala and Belize and extends north into the Gulf of Mexico. The Yucatán was a part of the ancient Mayan civilization and is still home to many Maya people.

Middle America is not a unified realm but is characterized by a high level of political and cultural diversity. A diverse mix of people—with Amerindian (people native to the Americas), African, European, and Asian ethnic backgrounds—make up the cultural framework. This realm is often associated with the term “Latin America” because of the dominance of colonialism from European countries such as Spain, France, and Portugal, where the people speak a Latin-based language. The truth is that Latin is not an active language, and Middle America has created its own cultural identity in spite of the impact of colonialism, and the realm can be defined by its people and their activities as much as by its physical environment.

7.1 Introducing the Realm

Learning Objectives

- Define the differences between the rimland and the mainland.

- Summarize the impact of European colonialism on Middle America.

- Distinguish between the Mayan and Aztec Empires and identify which the Spanish defeated.

- Describe how the Spanish influenced urban development.

A. Physical Geography

Middle America has various types of physical landscapes, including volcanic islands and mountain ranges. Tectonic action at the edge of the Caribbean Plate has brought about volcanic activity, creating many of the islands of the region as volcanoes rose above the ocean surface. The island of Montserrat is one such example. The volcano on this island has continued to erupt in recent years, showering the island with dust and ash and making habitation difficult. Many of the other low-lying islands, such as the Bahamas, were formed by coral reefs rising above the ocean surface. Tectonic plate activity not only has created volcanic islands but also is a constant source of earthquakes that continue to be a problem for the Caribbean community.

The republics of Central America extend from Mexico to Colombia and form the final connection between North America and South America. The Isthmus of Panama, the narrowest point between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, serves as a land bridge between the continents. The backbone of Central America is mountainous, with many volcanoes located within its ranges. Much of the Caribbean and all of Central America are located south of the Tropic of Cancer and are dominated by tropical type A climates. The mountainous areas have varied climates, with cooler climates located at higher elevations. Mexico has extensive mountainous areas with two main ranges in the north and highlands in the south. There are no landlocked countries in this realm, and coastal areas have been exploited for fishing and tourism development.

B. Rimland and Mainland

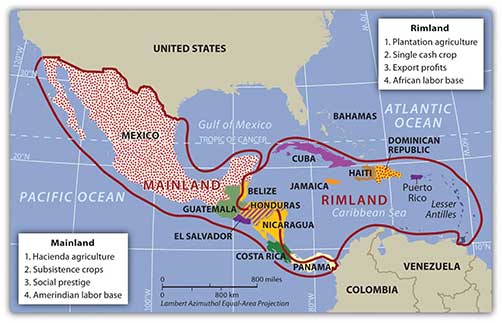

Using a regional approach to the geography of a realm helps us compare and contrast a place’s features and characteristics. Location and the physical differences explain the division of Middle America into two geographic areas according to occupational activities and colonial dynamics: the rimland, which includes the Caribbean islands and the Caribbean coastal areas of Central America, and the mainland, which includes the interior of Mexico and Central America.

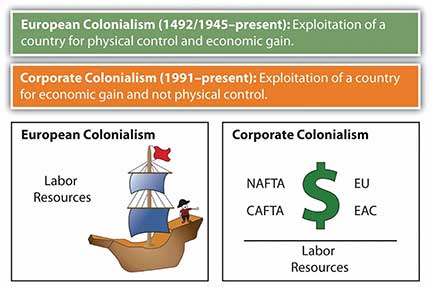

Colonialism thrived in the rimland because it consists mainly of islands and coastal areas that were accessible to European ships. Ships could easily sail into a cove or bay to make port and claim the island for their home country. After an island or coastal area was claimed, there was unimpeded transformation of the area through plantation agriculture. On a plantation, local individuals were subjugated as servants or slaves. The land was planted with a single crop—usually sugarcane, tobacco, cotton, or fruit—grown for export profits. Most of these crops were not native to the Americas but were brought in during colonial times. European diseases killed vast numbers of local Amerindian laborers, so slaves were brought from Africa to do the work. Plantation agriculture in the rimland was successful because of the import of technology, slave labor, and raw materials, as well as the export of the harvest to Europe for profit.

Plantation agriculture changed the rimland. The local groups were diminished because of disease and colonial subjugation, and by the 1800s most of the population was of African descent. Native food crops for consumption gave way to cash crops for export. Marginal lands were plowed up and placed into the plantation system. The labor was usually seasonal: there was a high demand for labor at peak planting and harvest times. Plantations were generally owned by wealthy Europeans who may or may not have actually lived there.

The mainland, consisting of Mexico and the interior of Central America, diverged from the rimland in terms of both colonial dynamics and agricultural production. The interior lacked the easy access to the sea that the rimland enjoyed. As a result, the hacienda style of land use developed. This Spanish innovation was aimed at land acquisition for social prestige and a comfortable lifestyle. Export profits were not the driving force behind the operation, though they may have existed. The indigenous workers, who were poorly paid if at all, were allowed to live on the haciendas, working their own plots for subsistence. African slaves were not prominent in the mainland.

In the mainland, European colonialists would enter an area and stake claims to large portions of the land, often as much as thousands or even in the millions of acres. Haciendas would eventually become the main landholding structure in the mainland of Mexico and many other regions of Middle America. In the hacienda system, the Amerindian people lost ownership of the land to the European colonial masters. Land ownership or the control of land has been a common point of conflict throughout the Americas where land transferred from a local indigenous ownership to a colonial European ownership.

The plantation and hacienda eras are in the past. The abolition of slavery in the later 1800s and the cultural revolutions that occurred on the mainland challenged the plantation and hacienda systems and brought about land reform. Plantations were transformed into either multiple private plots or large corporate farms. The hacienda system was broken up, and most of the hacienda land was given back to the people, often in the form of an ejidos system, in which the community owns the land but individuals can profit from it by sharing its resources. The ejidos system has created its own set of problems, and many of the communally owned lands are being transferred to private owners.

The agricultural systems changed Middle America by altering both the systems of land use and the ethnicity of the population. The Caribbean Basin changed in ethnicity from being entirely Amerindian, to being dominated by European colonizers, to having an African majority population. The mainland experienced the mixing of European culture with the Amerindian culture to form various types of mestizo groups with Hispanic, Latino, or Chicano identities.

C. The European Invasion

European colonialism had an immense effect on the rest of the world. Among other things, colonialism diffused European languages and the Christian religion. Consider how European colonialism altered language and religion in the Americas. The two main European countries to colonize Middle and South America were Spain and Portugal, which are predominantly Roman Catholic. Latin Mass has been a tradition in the Roman Catholic Church, and the Latin-based Romance languages of Spanish and Portuguese are now the most widely used languages in Middle and South America. This is where the term Latin America originated for this realm, and the name is still widely used. Today, however, Middle America is a more accurate term for the region between the United States and South America, and South America is the appropriate name for the southern continent, in spite of the connection to Latin-based languages.

European colonialism impacted Middle America in more ways than language and religion. Before Christopher Columbus arrived from Europe, the Americas did not have animals such as horses, donkeys, sheep, chickens, and domesticated cattle. This meant there were no large draft animals for plowing fields or carrying heavy burdens. The concept of the wheel, which was so prominent in Europe, was not found in use in the Americas. Food crops were also different: the potato was an American food crop, as were corn, squash, beans, chili peppers, and tobacco. Europeans brought other food crops—either from Europe itself or from its colonies—such as coffee, wheat, barley, rice, citrus fruits, and sugarcane. Besides food crops, building methods, agricultural practices, and even diseases were exchanged. Since it occurred after the arrival of Columbus in the late 15th century, this widespread transfer of plants, animals, diseases, and technology is referred to as the Columbian Exchange.

The Spanish invasion of Middle America following Columbus had some devastating consequences for the indigenous populations. It has been estimated that fifteen to twenty million people lived in Middle America when the Europeans arrived, but after a century of European colonialism, only about 2.5 million remained. Through warfare, disease, and enslavement, the local populations were decimated. Only a small number of people still claim Amerindian heritage in the Caribbean Basin, and some argue that these few are not indigenous to the Caribbean but are descendants of slaves brought from South America by European colonialists.

D. The Maya and the Aztec

Though the region of Mexico has been inhabited for thousands of years, one of the earliest cultures to develop into a civilization with large cities was the Olmec, which was believed to be the precursor to the later Mayan Empire. The Olmec flourished in the south-central regions of Mexico from 1200 BCE to about 400 BCE. Anthropologists call this region of Mexico and northern Central America Mesoamerica. It is considered to be the region’s cultural hearth because it was home to early human civilizations. The Maya established a vast civilization after the Olmec, and Mayan stone structures remain as major tourist attractions. The classical era of the Mayan civilization lasted from 300 to 900 CE and was centered in the Yucatán Peninsula region of Mexico, Belize, and Central America. Guatemala was once a large part of this vast empire, and Mayan ruins are found as far south as Honduras. During the classical era, the Maya built some of the most magnificent cities and stone pyramids in the Western Hemisphere. The city-states of the empire functioned through a sophisticated religious hierarchy. The Mayan civilization made advancements in mathematics, astronomy, engineering, and architecture. They developed an accurate calendar based on the seasons and the solar system. The extent of their immense knowledge is still being discovered. The descendants of the Maya people still exist today, but their empire does not.

The Toltec, who controlled central Mexico briefly, came to power after the classical Mayan era. They also took control of portions of the old Mayan Empire from the north. The Aztec federation replaced the Toltec and Maya as the dominant civilization in southern Mexico. The Aztec, who expanded outward from their base in central Mexico, built the largest and greatest city in the Americas of the time, Tenochtitlán, with an estimated population of one hundred thousand. Tenochtitlán was located at the present site of Mexico City, and it was from there the Aztec expanded into the south and east to create an expansive empire. The Aztec federation was a regional power that subjugated other groups and extracted taxes and tributes from them. Though they borrowed ideas and innovations from earlier groups such as the Maya, they made great strides in agriculture and urban development. The Aztec rose to dominance in the fourteenth century and were still in power when the Europeans arrived.

E. Spanish Conquest of 1519–21

After the voyages of Columbus, the Spanish conquistadors came to the New World in search of gold, riches, and profits, bringing their Roman Catholic religion with them. Zealous church members sought to convert the “heathens” to their religion. One such conquistador was Hernán Cortés, who, with his 508 soldiers, landed on the shores of the Yucatán in 1519. They made their way west toward the Aztec Empire. The wealth and power of the Aztecs attracted conquistadors such as Cortés, whose goal was to conquer. Even with metal armor, steel swords, sixteen horses, and a few cannons, Cortés and his men did not challenge the Aztecs directly. The Aztec leader Montezuma II originally thought Cortés and his men were legendary “White Gods” returning to recover the empire. Cortés defeated the Aztecs by uniting the people that the Aztecs had subjugated and joining with them to fight the Aztecs. The Spanish conquest of the Aztec federation was complete by 1521.

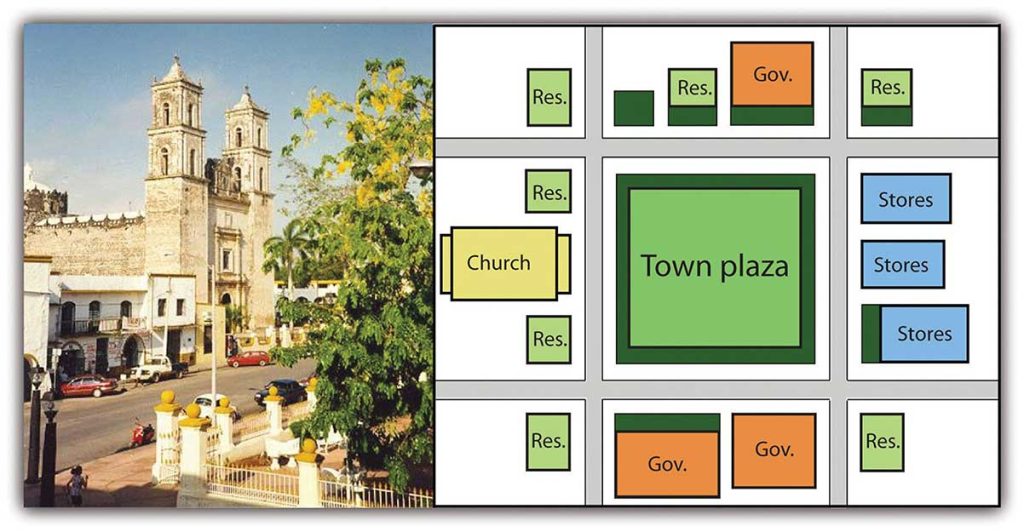

F. The Spanish Colonial City

As the Spanish established urban centers in the New World, they structured each town after the Spanish pattern, with a plaza in the center. Around the plaza on one side was the church (Roman Catholic). On the other sides were government offices and stores. Residential homes filled in around them. This pattern can still be seen in almost all the cities built by the Spanish in Middle and South America. The Catholic Church not only was located in the center of town but also was a supreme cultural force shaping and molding the Amerindian societies conquered by the Spanish.

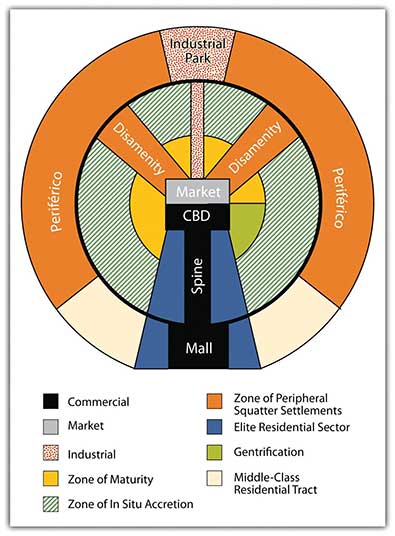

In Spain, the cultural norm was to develop urban centers wherever administration or military support was needed. Spanish colonizers followed a similar pattern in laying out the new urban centers in their colonies. Extending out from the city center (where the town plaza, government buildings, and church were located) was a commercial district that was the backbone of this model. Expanding out on each side of the spine was a wealthy residential district for the upper social classes, complete with office complexes, shopping districts, and upper-scale markets.

Surrounding the central business district (CBD) and the spine of most cities in Middle and South America are concentric zones of residential districts for the lower, working, and middle classes and the poor. The first zone, the zone of maturity, has well-established middle-class residential neighborhoods with city services. The second concentric zone, the zone of transition (in situ accretion), has poorer working-class districts mixed with areas with makeshift housing and without city services. The outer zone, the peripheral zone (Spanish, periférico), is where the expansion of the city occurs, with makeshift housing and squatter settlements. This zone has little or no city services and functions on an informal economy. This outer zone often branches into the city, with slums known as favelas or barrios that provide the working poor access to the city without its benefits. Impoverished immigrants that arrive in the city from the rural areas often end up in the city’s outer periphery to eke out a living in some of the worst living conditions in the world.

Cities in this Spanish model grow by having the outer ring progress to the point where eventually solid construction takes hold and city services are extended to accommodate the residents. When this ring reaches maturity, a new ring of squatter settlements emerges to form a new outer ring of the city. The development dynamic is repeated, and the city continues to expand outward. The urban centers of Middle and South America are expanding at rapid rates. It is difficult to provide public services to the outer limits of many of the cities. The barrios or favelas become isolated communities, often complete with crime bosses and gang activities that replace municipal security.

Key Takeaways

- Haciendas were located chiefly in the mainland and plantations were located mainly in the rimland.

- Both the hacienda and the plantation structures of agriculture altered the ethnic makeup of their respective regions. The rimland had an African labor base, and the mainland had an Amerindian labor base.

- In their quest for wealth, Spanish conquistadors destroyed the Aztec Empire and colonized the Middle American mainland. Much historical knowledge was lost with the demise of the learned class of the Aztec Empire.

- Europeans introduced many new food crops and domesticated animals to the Americas and in turn brought newly discovered agricultural products from America back to Europe. This is known as the Columbian Exchange.

- The Spanish introduced the same style of urban planning to the Americas that was common in Spain. Many cities in Middle and South America were patterned after Spanish models.

7.2 Mexico

Learning Objectives

- Describe the physical geography of Mexico, identifying the core and peripheral areas.

- Outline the socioeconomic classes in Mexico and explain the ethnic differences of each.

- Explain how the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and maquiladoras have influenced the economic and employment situations in Mexico.

- Understand how the drug cartels have become an integrated part of the Mexican economy and political situation.

A. Physical Characteristics

Mexico is the eighth-largest country in the world and is about one-fifth the size of the United States. One of Mexico’s prominent geographical features is the world’s longest peninsula, the 775-mile-long Baja California Peninsula, which lies between the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of California (also known as the Sea of Cortez). The Baja California Peninsula includes a series of mountain ranges called the Peninsular Ranges.

The Tropic of Cancer cuts across Mexico, dividing it into two different climatic zones: a temperate zone to the north and a tropical zone to the south. In the northern temperate zone, temperatures can be hot in the summer, often rising well above 80 °F, but considerably cooler in the winter. By contrast, temperatures vary very little from season to season in the tropical zone, with average temperatures hovering very close to 80 °F year-round. Temperatures in the south tend to vary as a function of elevation.

Mexico is characterized by a great variety of climates, including areas with hot humid, temperate humid, and arid climates. There are mountainous regions, foothills, plateaus, deserts, and coastal plains, all with their own climatic conditions. For example, in the northern desert portions of the country, summer and winter temperatures are extreme. Temperatures in the Sonoran and Chihuahuan Deserts exceed 110 °F, while in the mountainous areas snow can be seen at higher elevations throughout the year.

Two major mountain ranges extend north and south along Mexico’s coastlines and are actually extensions of southwestern US ranges. The Sierra Madre Occidental, an extension of the Sierra Nevada range, runs about 3,107 miles along the west coast, with peaks higher than 9,843 feet. The Sierra Madre Oriental is an extension of the Rocky Mountains and runs 808 miles along the east coast. Between these two mountain ranges lies a group of broad plateaus, including the Mexican Plateau, or Mexican Altiplano (a wide valley between mountain ranges). The central portions, with their rolling hills and broad valleys, include fertile farms and productive ranch land. The Mexican Altiplano is divided into northern and southern sections, with the northern section dominated by Mexico’s most expansive desert, the Chihuahuan Desert.

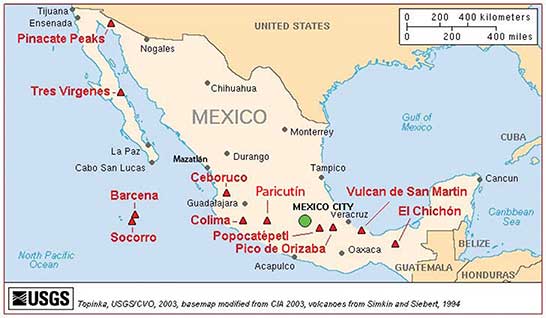

Another prominent mountain range is the Cordillera Neovolcánica range, which as its name suggests, is a range of volcanoes that runs nearly 620 miles east to west across the central and southern portion of the country. Geologically speaking, this range represents the dividing line between North and Central America. The peaks of the Cordillera Neovolcánica can reach higher than 16,404 feet in height and are snow covered year-round.

Copper Canyon, in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua, is about seven times larger than the Grand Canyon. Copper Canyon was formed by six rivers flowing through a series of twenty different canyons. Besides covering a larger area than the Grand Canyon, at its deepest point, Copper Canyon is 1,462 feet deeper than the Grand Canyon.

Though sandy beaches often come to mind when thinking about Mexico, the mountainous regions are home to pine-oak forests. More than a quarter of Mexico’s landmass is covered in forests; as a result, timber is an important natural resource. Mexico ranks fourth in the world for biodiversity; it has the world’s largest number of reptile species, ranks second for mammals, and ranks fourth for the number of amphibian and plant species. It is estimated that more than 10 percent of the world’s species live here. Forest depletion is a key environmental concern, but timber remains an important natural resource.

Three tectonic plates underlie Mexico, making it one of the most seismically active regions on earth. In 1985, an earthquake centered off Mexico’s Pacific coast killed more than ten thousand people in Mexico City and did significant damage to the city’s infrastructure.

Many of Mexico’s natural resources lie beneath the surface. Mexico is rich in natural resources and has robust mining industries that tap large deposits of silver, copper, gold, lead, and zinc. Mexico also has a sizable supply of salt, fluorite, iron, manganese, sulfur, phosphate, tungsten, molybdenum, and gypsum. Natural gas and petroleum also make the list of Mexico’s natural resources and are important export products to the United States. There has been some concern about declining petroleum resources; however, new reserves are being found offshore in the Gulf of Mexico.

Though only about 13 percent of Mexico’s land area is cultivated, favorable climatic conditions mean that food products are also an important natural resource both for export and for the feeding the country’s sizable population. Tomatoes, maize (corn), vanilla, avocado, beans, cotton, coffee, sugarcane, and fruit are harvested in sizable quantities. Of these, coffee, cotton, sugarcane, tomatoes, and fruit are primarily grown for export, with most products bound for the United States.

Mexico has very pronounced wet and dry seasons. Most of the country receives rain between June and mid-October, with July being the wettest month. Much less rain occurs during the other months: February is usually the driest month. More importantly, Mexico lies in the middle of the hurricane belt, and all regions of both coasts are at risk for these storms between June and November. Hurricanes along the Pacific coast are much less frequent and less violent than those along Mexico’s Gulf and Caribbean coasts. Hurricanes can cause extensive damage to infrastructure along the coasts where major tourist resorts are located. Mexico’s extensive and beautiful coastlines provide an important boon to the nation’s tourism industry.

B. The Core versus the Periphery

The Mexican economy is a mix of modern industry, agriculture, and tourism. Current estimates indicate that the service sector makes up about 60 percent of the economy, followed by the industrial sector at 33 percent. Agriculture represents just above 4 percent. Per capita income in Mexico is about one-third of what it is in the United States. The Mexican labor force is estimated at forty-six million individuals; 14 percent of the labor force work in agriculture, 23 percent in the industrial sector, and 62 percent in the service sector.

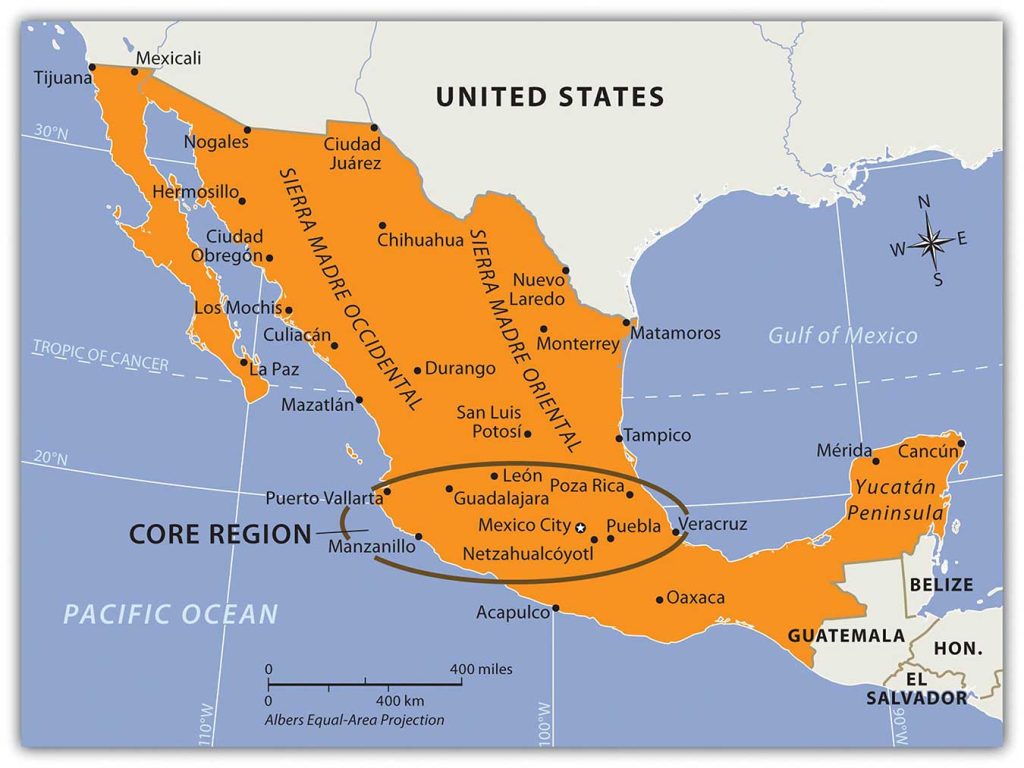

Mexico is an example of a country with a clear core-periphery spatial relationship. Mexico City and its surrounding metropolitan centers represent the country’s core: the center of activity, industry, wealth, and power. Industries and manufacturing have been traditionally located in this region. The core region has most of the country’s 110 million people (as of 2010). Mexico’s population is about 77 percent urban, with the largest urban areas found in the core region.

Mexico City is one of the largest cities in the world and anchors the core region of Mexico. In 2010, the official population of Mexico City was about eighteen million, but unofficial population estimates are as high as thirty million. The actual population of Mexico City is unknown because of the hundreds of slums that surround the city on the slopes of the central valley. Mexico City is growing at a rate of more than one thousand people per day through a combination of the number of births and the number of migrants. The lure of opportunities and advantages still pulls migrants to the city in search of a better life. Higher populations tax the resources in rural areas, where jobs and opportunities are hard to find. This push-pull relationship creates a strong rural-to-urban shift in Mexico. This same trend is found throughout the developing world.

Mexico City is a historic and vibrant city, but is not without problems. At higher than seven thousand feet in elevation, it is located between two mountain ranges. Air pollution is severe and is augmented by frequent temperature inversions that trap pollution over the city. Fresh water is in short supply, and wastewater from sewage is discharged into lakes down the valley. Amerindians who live by these lakes or on the islands have to deal with the pollution. Because about four to five million inhabitants of Mexico City have no utilities, human waste buildup has become a challenge. Fresh water is pumped into the city through pipelines from across the mountains. Leakage and inadequate maintenance cause a large percentage of the water to be lost before it can be used in the city. Water is also drawn from underground aquifers beneath the city, which has caused parts of the city to sink as much as two feet, causing serious structural damage to historic buildings.

C. Mexican Social Order

The early European control of the land, the economy, and the political system created conflict for the people of Mexico. The country has experienced domination followed by revolution at various times, starting with colonial domination, then economic domination, and lastly political domination. The result was a mixing of Europeans and Amerindians, creating the current mestizo mainstream society. Mestizos make up about 60 percent of the current population, Europeans make up about 9 percent, and Amerindians make up about 30 percent. More than sixty indigenous languages spoken by Amerindian groups are recognized in Mexico.

Mexican society is regionally and ethnically diverse, with sharp socioeconomic divisions. Many rural communities have strong ties with their regions and are often referred to as patrias chicas (“small homelands”), which helps to perpetuate the cultural diversity. The large number of indigenous languages and customs, especially in the southern parts of Mexico, further emphasize cultural diversity. Idigenismo (“pride in the indigenous heritage”) has been a unifying theme of Mexico since the 1930s. However, daily life in Mexico can be dramatically different according to socioeconomic class, gender, ethnicity, rural or urban settlements, and other cultural differences. A peasant farmer in the rainforests of the Yucatán will lead a very different life than a museum curator in Mexico City or a lower-middle-class auto factory worker in Monterrey.

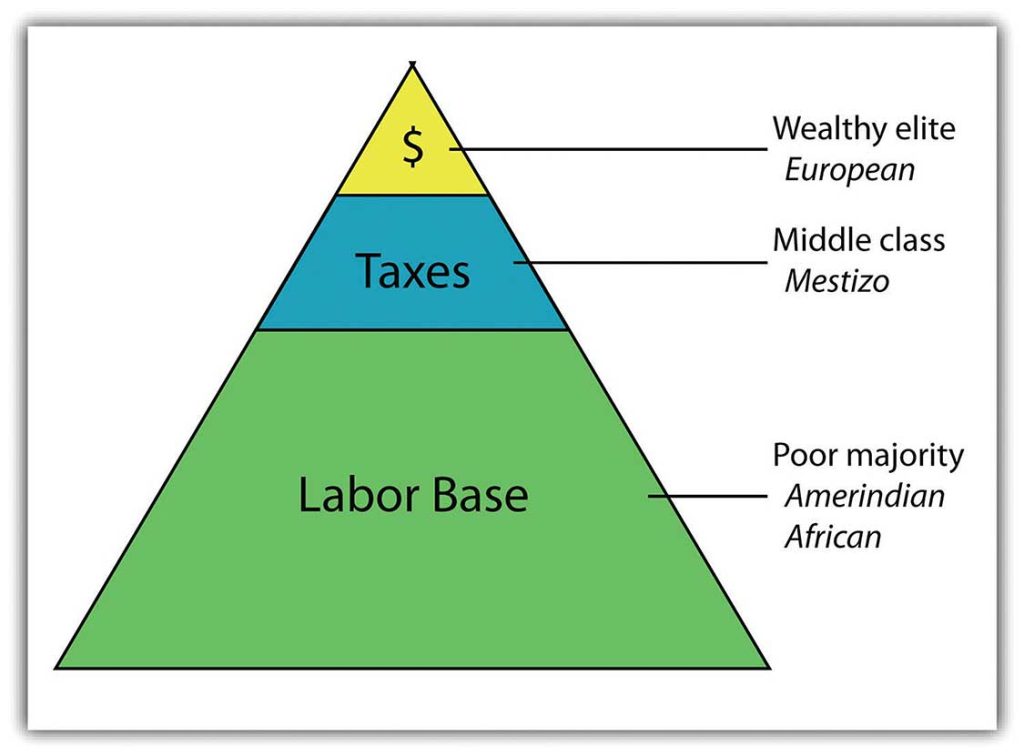

Those of European descent are at the top of the pyramid and control a higher percentage of the wealth and power even though they are a minority of the population. The small middle class is largely mestizo, including managers, business people, and professionals. The working poor make up most of the population at the bottom of the pyramid. The lower class contains the highest percentage of people of Amerindian descent or, in the case of the Caribbean, African descent.

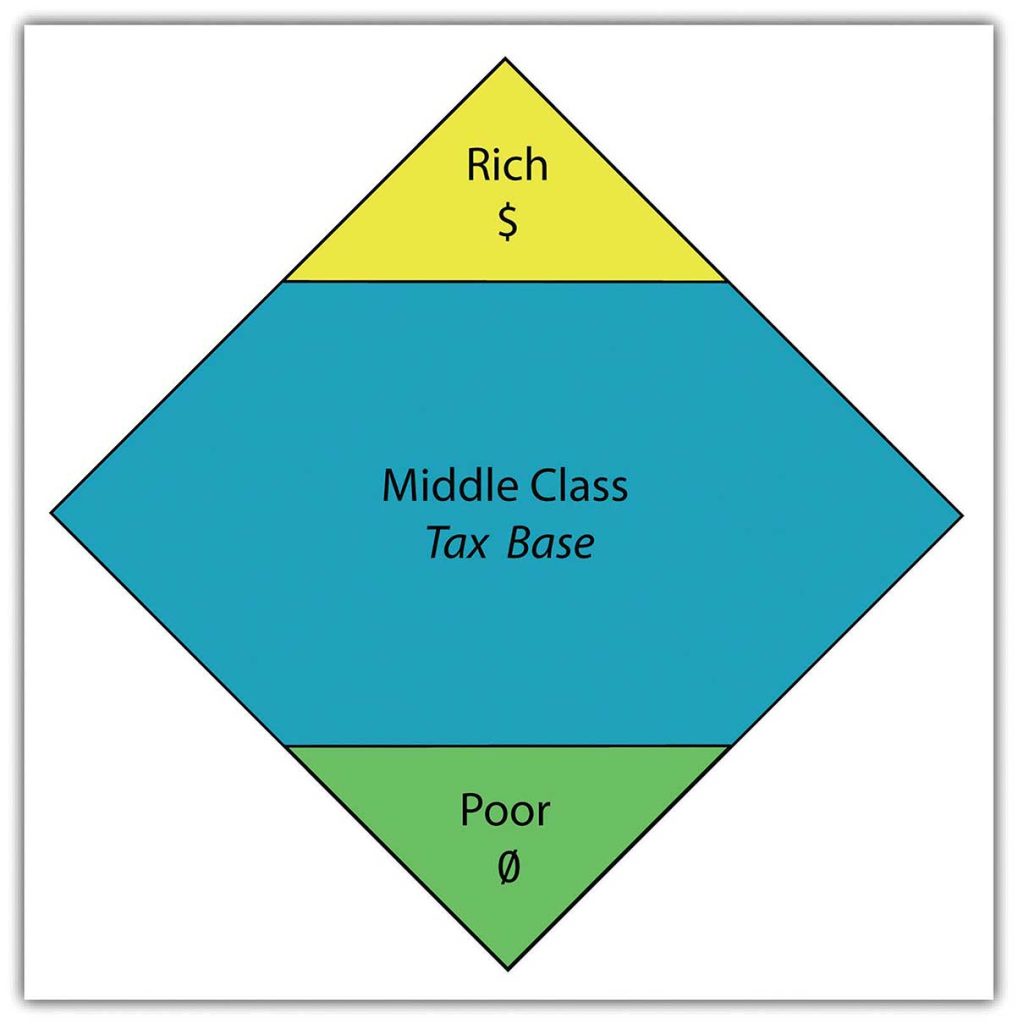

The most desirable type of social structure is illustrated by a diamond shape: in the middle is a large, employed middle class that can pay most of the taxes and purchase consumer goods that help bolster the economy. The narrow top is made up of the richest, and the narrow bottom is made up of the poorest

.

Unfortunately, this optimal type of social structure does not always materialize in the manner hoped for. As an example, a goal of the economic planners of the United States has been to create a wide social profile. Unfortunately, in recent decades the US middle class has been declining, and the wealthy class and the working-class poor have increased. In Mexico, about 40 percent of the population lives in poverty.

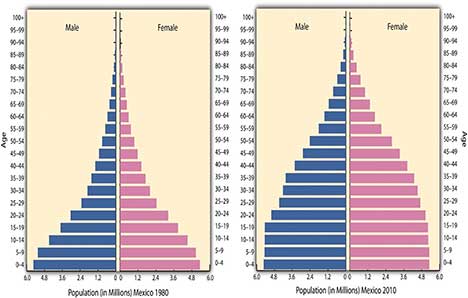

Over the course of the past century, the people of Mexico have been working through a demographic transition. As the rural regions of Mexico continued to have a high fertility rate, death rates declined, and the country’s population grew exponentially. In 1970, the population of Mexico was about fifty million. By the year 2000, it had doubled to more than one hundred million. However, the population estimate for 2010 was just greater than 110 million. As Mexico urbanizes and industrializes, family size and fertility rates have been in decline, and population growth has slowed.

D. NAFTA and Maquiladoras

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), is a 1994 economic agreement between Canada, the United States, and Mexico that eliminated or reduced the tariffs, taxes, and quotas between the countries to create the world’s largest trading bloc to compete with the European Union and the global economy. This theoretically allows more corporate investments across borders and increases foreign ownership of business facilities. It stimulated a shift in the location of industrial activity and in the migration patterns of people in Mexico. Capitalizing on the old industrial locations of northern Mexico, such as Monterrey, corporations started to relocate manufacturing plants from the United States to the Mexican side of the border to take advantage of Mexico’s low-cost labor. The aspect of cheaper labor was a benefit understood to bolster corporate profits and reduce product costs. The United States is one of the world’s largest consumer markets, so these manufacturing plants, called maquiladoras (also known as maquilas), could benefit both countries.

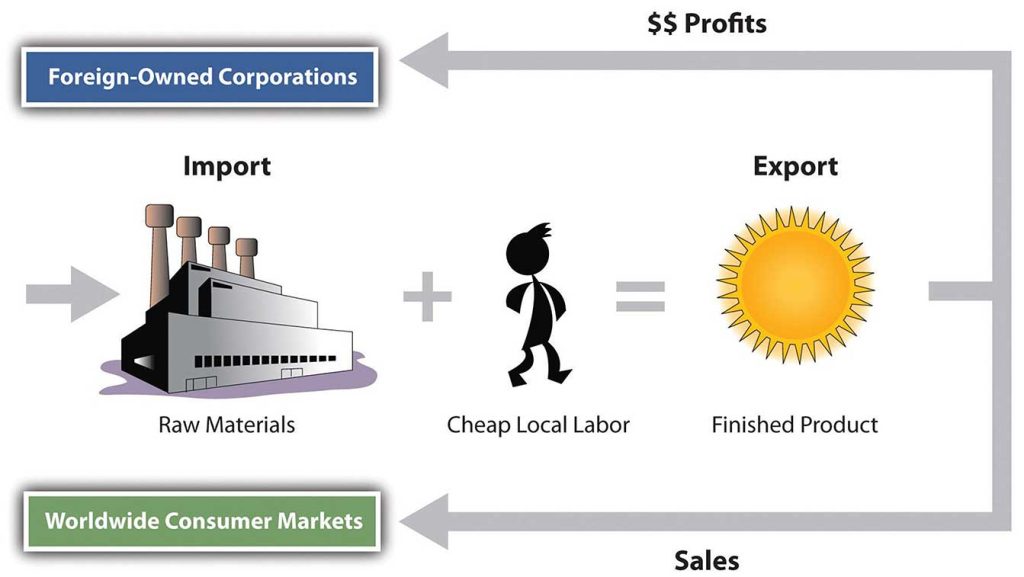

Maquiladoras are foreign-owned factories that import most of the raw materials or components needed for the products they manufacture, assemble, or process with local cheap labor, and then they export the finished product for profit. US corporations own more than half the maquiladoras in Mexico, and about 80 percent of the finished goods are exported back to the United States. Although most maquiladoras are located near the US-Mexican border, additional factories are located around Monterrey and other cities with easy access to the United States. A major trade corridor is developing between Monterrey and Dallas/Ft. Worth, which acts as a doorway to the US markets.

Thousands of maquiladoras flourish along the US-Mexican border, although the Mexican government has also promoted maquiladoras in other parts of Mexico. Maquiladoras provide jobs for workers in Mexico and provide cheaper goods for US consumers. However, this system has inherent problems. Labor unions in the United States complain that the high-paying industrial jobs that support the US middle class are being lost to cheap Mexican labor. Labor laws in Mexico are less rigorous than US laws, allowing for longer work hours and fewer benefits for maquiladora employees. In addition, pollution standards in Mexico are not as restrictive as those in the US, giving rise to environmental concerns.With the rapid increase in employment along the border, many of the people who work in the factories do not have adequate housing or utilities. Extensive slum areas have grown around maquiladoras, which have little law enforcement, high crime, and few services.

The US-Mexican border region has become a strong pull factor, enticing poor people who seek greater opportunities and advantages to move from Mexico City and other southern regions of Mexico to the border region to look for work. When they do not find work, they are tempted to cross the US border illegally. The United States is considered a land of opportunity and attracts immigrants—both legal and illegal—from Mexico.

Critics of NAFTA claim that the term free trade really means corporate trade. NAFTA is also viewed as a component of globalization in the form of corporate colonialism, which only benefits those wealthy enough to hold investments at the corporate level. The exploitation of cheap labor has caused undue immigration across the US-Mexican border, bringing millions of illegal workers into the United States. The Mexican government has not adequately addressed Mexico’s economic conditions to provide jobs and opportunities for the people or to use the wealth held or controlled by the elite minority to enhance economic opportunities for the middle- and lower-class majority.

E. Illegal Drug Trafficking in Mexico

The illegal drug trade is a multibillion-dollar industry, and Mexico has traditionally been the transitional area or stop-off point between the South American drug producing areas and entrance into US markets. Cocaine, marijuana, and more recently heroin were produced in the Andes Mountains of South America and shipped north to the United States. Colombian cartels were once the main controllers of illegal drugs in the Western Hemisphere, but in recent decades, organized crime units in Mexico have muscled in on the control of drugs coming through Mexico, making deals with their South American counterparts to become the main traffickers of drugs into the United States, and the influence and power of Mexican drug cartels has increased immensely since the demise of the Colombian cartels in the 1990s. Enormous profits fuel the competition for control.

Just as the United States has declared a war on drugs and has used its Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) as a main arm in combating the industry, the Mexican government has been engaged in its own internal war against the illegal drug trade. The battles between the drug cartels and the Mexican government have created a serious internal conflict in the country, killing thousands of innocent bystanders in the cross fire. Bribes, payoffs, and corruption have been difficult to battle in a country with a high percentage of the population living in poor conditions.

Key Takeaways

- Mexico possesses extensive natural resources that provide for a wide range of biodiversity and economic activities.

- Mexico portrays a clear core-periphery spatial relationship. Mexico City and its urban neighbors anchor the core, while the northern border region and states such as Chiapas represent the rural periphery.

- People of European heritage continue to hold positions of power and privilege in Mexico’s

socioeconomic class structure. Amerindian populations exist at the lowest level with the fewest economic opportunities. - Economic reforms that coincide with NAFTA have greatly enhanced the industrial capacity of Mexico and helped integrate the country into the global economy.

- Mexican drug traffickers have become the major controllers of illegal drugs entering the United States from the south. Drug cartels in Mexico reap enormous profits and have become a major problem for the Mexican government and the country.

7.3 Central America

Learning Objectives

- Describe how the physical environment has affected human activity in Central America.

- Outline the various ways in which the United States has affected the region.

- Explain the similarities and the differences among the Central American republics.

- Understand how the Panama Canal came to be constructed and what role the United States has played in Panama.

A. Physical Environment

Central America is a land bridge connecting the North and South American continents, with the Pacific Ocean to its west and the Caribbean Sea to its east. A central mountain chain dominates the interior from Mexico to Panama. The coastal plains of Central America have tropical and humid type A climates. In the highland interior, the climate changes with elevation. As one travels up the mountainsides, the temperature cools. Only Belize is located away from this interior mountain chain. Its rich soils and cooler climate have attracted more people to live in the mountainous regions than along the coast.

The volcanic activity along the central mountain chain over time has provided rich volcanic soils in the mountain region, which has attracted people to work the land for agriculture. Central America has traditionally been a rural peripheral economic area in which most of the people have worked the land. Family size has been larger than average, and rural-to-urban shift dominates the migration patterns as the region urbanizes and industrializes. Natural disasters, poverty, large families, and a lack of economic opportunities have made life difficult in much of Central America.

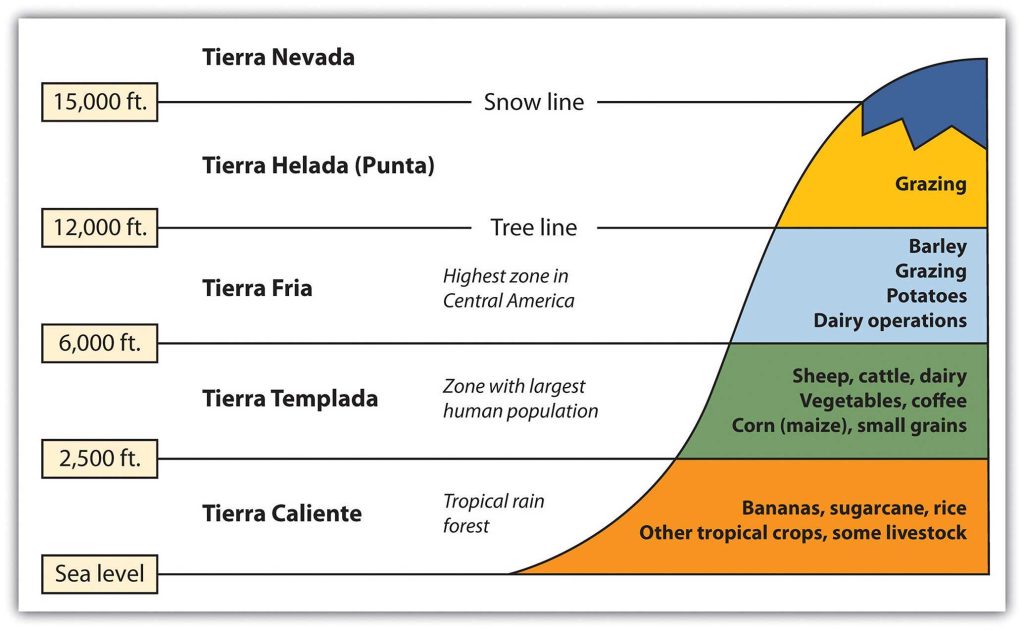

Altitudinal Zonation

High mountains ranges run the length of Central and South America. The Andes Mountains of South America are the longest mountain chain in the world, and a large section of this mountain range is in the tropics. Tropical regions usually have humid type A climates. What is significant in Latin America is that while the climate at the base of the Andes may be type A, the different zones of climate and corresponding human activity vary as one moves up the mountain in elevation. Mountains have different climates at the base than at the summit. Type H highland climates describe mountainous areas that exhibit different climate types at varying degrees of elevation.

Human activity varies with elevation, and the activities can be categorized into zones according to altitudinal zonation. Each zone has its own type of vegetation and agricultural activity suited to the climate found at that elevation. For every thousand-foot increase in elevation, temperature drops 3.6 ºF. In the tropical areas of Latin America, there are five established temperature-altitude zones. These five zones and their corresponding elevation ranges are listed below. Note that these elevation ranges are for locations near the equator. The upper elevation limit for each zone generally decreases as you move further from the equator.

From sea level to 2,500 feet, Tierra Caliente (Hot Land) are the humid tropical lowlands found on the coastal plains. The coastal plains on the west coast of Middle America are quite narrow, but they are wider along the Caribbean coast. Vegetation includes tropical rain forests and tropical commercial plantations. Food crops include bananas, manioc, sweet potatoes, yams, corn, beans, and rice. Livestock are raised at this level, and sugarcane is an important cash crop. Tropical diseases are most common, and large human populations are not commonly attracted to this zone.

From 2,500 to 6,000 feet, Tierra Templada (Temperate Land) is a zone with cooler temperatures than at sea level. This is the most populated zone of Latin America. Four of the seven capitals of the Central American republics are found in this zone. Just as temperate climates attract human activity, this zone provides a pleasant environment for habitation. The best coffee is grown at these elevations, and most other food crops can be grown here, including wheat and small grains.

6,000 to 12,000 feet Tierra Fria (Cold Land) is the highest zone found in Middle America. This zone is usually the limit of the tree line; few trees grow north of this zone. The shorter growing season and cooler temperatures found at these elevations are still adequate for growing agricultural crops of wheat, barley, potatoes, or corn. Livestock can graze and be raised on the grasslands. The Inca Empire of the Andes Mountains in South America flourished in this zone.

Some classify Tierra Helada (Frozen Land) as the “Puna” zone. At this elevation, there are no trees. The only human activity is the raising of livestock such as sheep or llama on any short grasses available in the highland meadows. Snow and cold dominate the zone. Central America does not have a tierra helada zone, but it is found in the higher Andes Mountain Ranges of South America.

There is little human activity in the Tierra Nevada (Snowy Land) above 15,000 feet. Permanent snow and ice is found here, and little vegetation is available. Many classification systems combine this zone with the tierra helada zone.

B. European Colonialism

Amerindian groups dominated Central America before the European colonial powers arrived. The Maya are still prominent in the north and make up about half the population of Guatemala. Other Amerindian groups are encountered farther south, and many still speak their indigenous languages and hold to traditional cultural customs. People of European stock or upper-class mestizos now control political and economic power in Central America. Indigenous Amerindian groups find themselves on the lower rung of the socioeconomic ladder.

During colonial times, the Spanish conquistadors dominated Central America with the exception of the area of Belize, which was a British colony called British Honduras until 1981. Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica were Spanish colonies and became independent of Spain in the 1820s. Panama was a part of Colombia and was not independent until the United States prompted an independence movement in 1903 to develop the Panama Canal. As is usually the case with colonialism, the main religion and the lingua franca of the Central American states are those of the European colonizers, in this case Roman Catholicism and Spanish. In some locations, the language and religion take on variant forms that mix the traditional with the European to create a unique local cultural environment.

C. People and Population

About 50 percent of the people of Central America live in rural areas, and because the economy is agriculturally based, family size has traditionally been large. Until the 1990s, family size averaged as high as six children. As the pressures of the postindustrial age have influenced Central America, average family size has been decreasing and is now about half that of the pre-1990s and is declining. For example, the World Bank reports that in Nicaragua the average woman has 2.68 children during her lifetime. Rural-to-urban shift is common, and as the region experiences more urbanization and industrialization, family size will decrease even more.

During the twentieth century, much of Central America experienced development similar to stage 2 of the index of economic development. An influx of light industry and manufacturing firms seeking cheap labor has pushed many areas into stage 3 development. The primate cities and main urban centers are feeling the impact of this shift.

Over the years, larger family sizes have created populations with a higher percentage of young people and a lower percentage of older people. Cities are often overwhelmed with young migrants from the countryside with few or no places to live. Rapid urbanization places a strain on urban areas because services, infrastructure, and housing cannot keep pace with population growth. Slums with self-constructed housing districts emerge around the existing urban infrastructure. The United States has also become a destination for people looking for opportunities or advantages not found in these cities.

CAFTA and Neocolonialism

Just as Canada, the United States, and Mexico signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) into law in 1994, the United States and five Central American states signed the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) in 2006. The agreement was signed by trade representatives from El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and the United States. The CAFTA-DR agreement, which includes the Dominican Republic, was ratified in 2007. In 2010, Costa Rica’s legislature approved a measure to join the agreement. CAFTA is supported by the same forces that advocated neocolonialism in other regions of the world.

CAFTA’s purpose is to reduce trade barriers between the United States and Central America, thus affecting labor, human rights, and the flow of wealth. During negotiations for CAFTA, US political forces cited CAFTA as a top priority and argued that it would help move forward the possibility of the larger Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), which would create a single market for the Americas.

Countries gain national wealth in the three main ways: by growing it, extracting it, or manufacturing it. These methods, however, contribute to a nation’s wealth only if the wealth stays within the country. With free-trade agreements such as NAFTA and CAFTA, the wealth gained from manufacturing, which has the highest value-added profits, does not stay in the country of production. Instead, the profits are carted off to the foreign corporation that controls the industrial factory. Multinational corporations see Central American countries as profitable sites for industrial; they can exploit cheap labor sources and at the same time provide jobs for local people. These advantages should result in lower product costs for consumers.

There have been protest marches and anti-CAFTA activities in many Central American countries. One of the primary arguments opponents to CAFTA make is that the wealth generated by the exploitation of the available cheap labor will not stay in Central America; instead, it will be removed by the wealthy core nations, just as European colonialism removed the wealth generated by the conquistadors and shipped it back to Europe.

Supporters of CAFTA claim that it provides jobs, infrastructure, and opportunities to the developing countries of Central America. In return, cheap consumer goods are available to the people. The globalized economy is a mixed game: on the one hand, consumer goods are inexpensive to purchase; on the other hand, the world’s wealth flows into the hands of a few people at the top and is not always shared with most of the people who contribute to it.

Key Takeaways

- Central America shares a similar climate type and physical features. It has enormous potential for tourism development. The political history of the region is quite diverse, with each republic experiencing different political and economic conditions.

- High population growth and rapid rural-to-urban shift has created higher unemployment rates and fewer economic opportunities. CAFTA was implemented to help multinational corporations tap into the cheap labor pool.

- The United States has had a major impact on this region both politically and economically. The United States has intervened in civil wars and invaded Panama. US companies have dominated much of the region’s fruit and coffee production. Most recently, the United States has supported industrial activities and the implementation of CAFTA.

7.4 The Caribbean

Learning Objectives

- Describe how the physical environment has affected human activity in the region.

- Outline the various ways in which colonialism has impacted the islands.

- Explain why the United States has an economic embargo against the socialist country of Cuba.

- Explain how tourism has become the main means of economic development for most of

the Caribbean. - Identify the main music genres that have emerged from the Caribbean.

The regions of Middle America and South America, including the Caribbean, follow similar colonial patterns of invasion, dominance, and development by outside European powers. The Caribbean Basin is often divided into the Greater Antilles and the Lesser Antilles (the bigger islands and the smaller islands, respectively). The Greater Antilles includes the four large islands of Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico. The Lesser Antilles are in the eastern and southern region. The Bahamas are technically in the Atlantic Ocean, not in the Caribbean Sea, but they are usually associated with the Caribbean region and are often affiliated with the Lesser Antilles. Middle America can be divided into two geographic areas according to occupational activities and colonial dynamics. The rimland includes the Caribbean islands and the Caribbean coastal areas of Central America. The mainland includes the interior of Mexico and Central America.

Many of the Caribbean islands experience the rain shadow effect. Jamaica has as much as a twenty-inch difference in rainfall between the north side and south side of the island because most of the rain falls on the north side, where the prevailing winds hit the island. The Blue Mountains in the eastern part of the island provide a rain shadow effect. Puerto Rico has a tropical rain forest on the northeastern part of the island, which receives a large amount of rainfall. The rain shadow effect creates semi-desert steppe conditions on the southwestern side of Puerto Rico because the southwestern side receives little rainfall. Low elevation islands such as the Bahamas do not receive as much rain because they are not high enough to affect the precipitation patterns of rain clouds.

A. European Colonialism in the Caribbean

The Spanish were not the only Europeans to take advantage of colonial expansion in the Caribbean: the English, French, Dutch, and other Europeans followed. Most of the European colonial countries were located on the west coast of Europe, which had a seafaring heritage. This included smaller countries such as Denmark, Sweden, and Belgium. The Caribbean Basin became an active region for European ships to enter and vie for possession of each island.

Many of the Caribbean islands changed hands several times before finally being secured as established colonies (Table 7.1). The cultural traits of each of the European colonizers were injected into the fabric of the islands they colonized; thus, the languages, religions, and economic activities of the colonized islands reflected those of the European colonizers rather than those of the native people who had inhabited the islands originally. The four main colonial powers in the Caribbean were the Spanish, English, Dutch, and French. Other countries that held possession of various islands at different times were Portugal, Sweden, and Denmark. The United States became a colonial power when they gained Cuba and Puerto Rico as a result of the Spanish-American War. The US Virgin Islands were purchased from Denmark in 1918. Sweden controlled the island of St. Barthelemy from 1784 to 1878 before trading it back to the French, who had been the original colonizer. Portugal originally colonized Barbados before abandoning it to the British.

Colonialism drastically altered the ethnic makeup of the Caribbean; Amerindians were virtually eliminated after the arrival of Africans, Europeans, and Asians. The current social hierarchy of the Caribbean can be illustrated by the pyramid-shaped graphic that was used to illustrate social hierarchy in Mexico. Those of European descent are at the top of the pyramid and control a higher percentage of the wealth and power even though they are a minority of the population. In the Caribbean, the middle class includes mulattos, or people with both African and European heritage, many of which include managers, businesspeople, and professionals. In some countries, such as Haiti, the minority mulatto segment of the population makes up the power base and holds political and economic advantage over the rest of the country while the working poor at the bottom of the pyramid make up most of the population. In the Caribbean, the lower economic class contains the highest percentage of people of African heritage.

Not only was colonialism the vehicle that brought many Africans to the Caribbean through the slave trade, but it brought many people from Asia to the Caribbean as well. Once slavery became illegal, the colonial powers brought indentured laborers to the Caribbean from their Asian colonies. Cuba was the destination for over one hundred thousand Chinese workers, so Havana can claim the first Chinatown in the Western Hemisphere. Laborers from the British colonies of India and other parts of South Asia arrived by ship in various British colonies in the Caribbean. At the present time, about 40 percent of the population of Trinidad can claim South Asian heritage and a large number follow the Hindu faith.

|

Colonizer |

European Colonies |

|

Spain |

Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico |

|

British |

Bahamas, Jamaica, Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Antigua, Dominica, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Grenada, Barbados, Virgin Islands, Trinidad and Tobago, Montserrat, Anguilla, St. Kitts and Nevis |

|

Dutch |

Curacao, Bonaire, Aruba, St. Eustatius, Saba and Sint Maarten (south half) |

|

French |

Haiti, Guadeloupe, Martinique, St. Martin (north half), St. Barthelemy |

|

United States |

Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, Cuba |

Table 1. Historical Caribbean Colonizers.

B. The Greater Antilles

Cuba: A Rimland Experience

The largest island in the Greater Antilles is Cuba, which was transformed by the power of colonialism, the transition to plantation agriculture, and a socialist revolution. Cuba is less than half the size of the US state of Oregon, but it has more than eleven million people, while Oregon has just over four million. The elongated island has the Sierra Maestra mountains on its eastern end, the Escambray Mountains in the center, and the Western Karst region in the west, near Viñales. Low hills and fertile valleys cover more than half the island. The pristine waters of the Caribbean that surround the island make for some of the most attractive tourism locations in the Caribbean region.

With the defeat of Spain in the Spanish-American War, the United States gained possession of the Spanish possessions of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines, and various other islands and thus became a colonial power. Cuba technically became independent in 1902 but remained under US influence for decades. Sugar plantations and the sugar industry came to be owned and operated by US interests, and wealthy Americans bought up large haciendas (large estates), farmland, and family estates, as well as industrial and business operations. Organized crime syndicates operated many of the nightclubs and casinos in Havana. As long as government leaders supported US interests, things went well with business as usual.

The Cuban Revolution

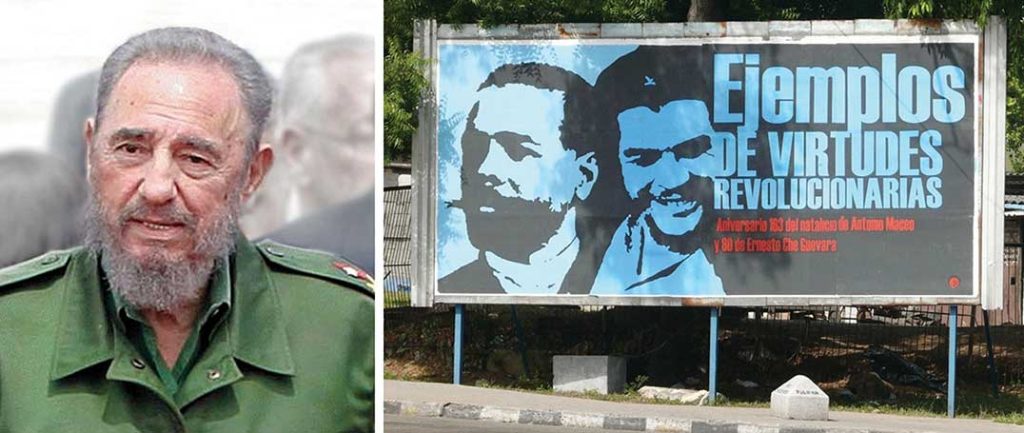

In January of 1934, with the encouragement of the US government, Fulgencio Batista led a coup that took control of the Cuban government. Fidel Castro, once a prisoner under Batista and having fled to Mexico in exile for a number of years, returned to Cuba to start a revolution. Joining him were his brother Raúl Castro and revolutionaries such as Che Guevara, an Argentinean doctor turned comrade-in-arms. Starting in the remote and rugged Sierra Maestras in the east, Castro rallied the support of the Cuban people. By the end of 1958, the Cuban Revolution brought down the US-backed Batista government. Castro gained power and had the support of most of the Cuban population.

Castro worked to recover Cuba for Cubans. The government cleared rampant gambling from the island, forcing organized crime operations to shut down or move back to the United States. Castro nationalized all foreign landholdings and the sugar plantations, as well as all the utilities, port facilities, and other industries. Foreign ownership of land and businesses in Cuba was forbidden. Large estates, once owned by rich US families, were taken over and recovered for Cuban purposes.

The US Embargo Era

Castro’s policy of seizing (nationalizing) businesses and property raised concerns in the United States. As a result, US president Dwight D. Eisenhower severed diplomatic relations with Cuba in 1960 and issued an executive order implementing a partial trade embargo to prohibit the importation of Cuban goods. Later presidents implemented a full-scale embargo, restricting travel and trade with Cuba.

To deter any further US plans of invading or destabilizing Cuba, Castro sought economic and military assistance from the Soviet Union. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 caused a downturn in Cuba’s economy. With the loss of Soviet aid, the 1990s were a harsh time for Cubans, a period of transition. Castro turned to tourism and foreign investment to shore up his failing economy. Tensions between the United States and Cuba did not improve. In 1996, the United States strengthened the trade embargo.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, Cuba emerged as the lone Communist state in the Americas. Castro was the longest-governing leader of any country in the world. He never kept his promises of holding free elections; instead, he cracked down on dissent and suppressed free speech. He turned over power to his brother Raúl in 2006. Fidel Castro died in late 2016.

A Post-Castro Cuba

With Fidel Castro no longer in power, Cuba’s future looks more positive but difficult. The island has natural resources, a great climate, and an excellent location but is also struggling economically. Cuba has a high literacy rate and has standardized health care, though medical supplies are often in short supply. The Cubans who live in dire poverty look to the future for relief. Personal freedoms have been marginal, and reforms are slowly taking place in the post-Fidel era. As the largest island in the Caribbean, Cuba has the potential to become an economic power for the region. There is vast US interest in regaining US dominance of the Cuban economy, and corporate colonialists would like to exploit Cuba’s economic potential. Keeping corporate colonialism out is what Fidel’s socialist experiment worked so hard to achieve, even at the expense of depriving the Cuban people of civil rights and economic reforms.

Cuba today is in transition from a socialist to a more capitalist economy and is counting on tourism for an added economic boost. With some of the finest beaches and the clearest waters in the Caribbean, Cuba is a magnet for tourists and water sports enthusiasts. Its countryside is full of wonders and scenic areas. The beautiful Viñales Valley in western Cuba has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its outstanding karst landscape and traditional agriculture as well as for its architecture, crafts, and music. Karst topography is made up of soluble rock, such as limestone, which in the Viñales Valley results in unusual bread loaf–shaped hills that create a scenic landscape attractive for tourism. This region is also one of Cuba’s best tobacco-growing areas and has great potential for economic development. The Cuban economy is banking on tourism to forge a path to a more prosperous future.

The Commonwealth of Puerto Rico

Populated for centuries by Amerindian peoples, the island of Puerto Rico was claimed by the Spanish Crown in 1493, following Columbus’s second voyage to the Americas. In 1898, after four hundred years of colonial rule, during which the indigenous population was nearly exterminated and African slave labor was introduced, Puerto Rico was ceded to the United States as a result of the Spanish-American War. Puerto Ricans were granted US citizenship in 1917. Popularly elected governors have served since 1948. In 1952, a constitution was enacted providing for internal self-government. In elections held in 1967, 1993, and 1998, Puerto Rican voters chose to retain the commonwealth status, although they were almost evenly split between total independence and becoming a US state. In a nonbinding referendum in 2012, for the first time a majority of voters in Puerto Rico favored becoming a US state, but that has not transpired as of 2016.

Puerto Rico is the smallest of the four islands of the Greater Antilles and is only slightly larger than the US state of Delaware. Puerto Rico’s population is about four million, similar to the population of Oregon. As US citizens, Puerto Ricans have no travel or employment restrictions anywhere in the United States, and about one million Puerto Ricans live in New York City alone. The commonwealth arrangement allows Puerto Ricans to be US citizens without paying federal income taxes, but they cannot vote in US presidential elections. The Puerto Rican Federal Relations Act governs the island and awards it considerable autonomy.

Puerto Rico has one of the most dynamic economies in the Caribbean Basin; still, about 60 percent of its population lives below the poverty line. A diverse industrial sector has far surpassed agriculture as the primary area of economic activity. Encouraged by duty-free access to the United States and by tax incentives, US firms have invested heavily in Puerto Rico since the 1950s, even though US minimum wage laws apply. Sugar production has lost out to dairy production and other livestock products as the main source of income in the agricultural sector. Tourism has traditionally been an important source of income, with estimated arrivals of more than five million tourists a year. San Juan is the number one port for cruise ships in the Caribbean outside Miami. The US government also subsidizes Puerto Rico’s economy with financial aid.

The future of Puerto Rico as a political unit remains unclear. Some in Puerto Rico want total independence, and others would like to become the fifty-first US state; the commonwealth status is a compromise. Puerto Rico is not an independent country as a result of colonialism. Many of the islands and colonies in the Caribbean Basin have experienced dynamics similar to Puerto Rico in that they are still under the political jurisdiction of a country that colonized it.

Hispaniola: The Dominican Republic and Haiti

Sharing the island of Hispaniola are the two countries of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The island became a possession of Spain under European colonialism after it was visited by Columbus in 1492 and 1493. French buccaneers settled on the western portion of Hispaniola and started growing tobacco and agricultural crops. France and Spain finally agreed to divide the island into two colonies: the western side would be French, and the eastern side would be Spanish.

The Dominican Republic holds the largest share of Hispaniola. A former Spanish colony, the Dominican Republic has weathered the storms of history to become a relatively stable democratic country. It is not, of course, without its problems. The Dominican Republic has long been viewed primarily as an exporter of sugar, coffee, and tobacco, but in recent years the service sector has overtaken agriculture as the economy’s largest employer. The mountainous interior and the coastal beaches are attractive to the tourism market, and tourism remains the main source of economic income. The economy is highly dependent on the United States, which is the destination for nearly 60 percent of its exports. Remittances from workers in the United States sent back to their families on the island contribute much to the economy. The country suffers from marked income inequality; the poorest half of the population receives less than one-fifth of the gross domestic product (GDP), while the richest 10 percent enjoys nearly 40 percent of GDP. High unemployment and underemployment remains an important long-term challenge. The Central American-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) came into play in March 2007, boosting investment and exports and reducing losses to the Asian garment industry. In addition, the global economic downturn has not helped the Dominican Republic.

Plantation agriculture thrived in Haiti during the colonial era, producing sugar, coffee, and other cash crops. The local labor pool was insufficient to expand plantation operations, so French colonists brought in thousands of African slaves to work the plantations, and people of African descent soon outnumbered Europeans. Haiti became one of the most profitable French colonies in the world with some of the highest sugar production of the time. A slave revolt that began in 1792 finally defeated the French forces, and Haiti became an independent country in 1804. It was the first country ever to be ruled by former slaves. However, the transition to a fully functional free state was difficult. Racked by corruption and political conflicts, few presidents in the first hundred years ever served a full term in office.

Haiti has had a difficult time finding political and economic stability. Haiti is the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere, and many Haitians live in dire poverty with few employment opportunities. An elite upper-class minority controls the bulk of the nation’s wealth.

C. Tourism and Economic Activity in the Rimland

The physical geography of the Caribbean region makes it a prime location for tourism. Its beautiful coastal waters and warm tropical climate draw in tourists from all over North America and the world. Tourism is the number one means of economic income for many places in the Caribbean Basin, and the tourist industry has experienced enormous growth in the last few decades. There has been strong growth in the number of cruise ships operating in the Caribbean. Cruise ships from the southern coasts of the United States ply their trade around the islands and coastal regions. Even the poorest country in the Caribbean, Haiti, has tried to attract cruise ships to its ports. The main restriction on cruise ship travel is the hurricane season, from June to November.

Even though tourism has become a vital economic component of the Caribbean Basin, in the long term, tourism creates many problems. Large cruise ships can overtax the environment; there have been occasions where there were actually more tourists than citizens on an island. An increase in tourist activity brings with it an increase in environmental pollution.

Most people in the Caribbean Basin live below the poverty line, and the investment in tourism infrastructure, such as exclusive hotels and five-star resorts, takes away resources that could be allocated to schools, roads, medical clinics, and housing. However, without the income from tourism, there would be no money for infrastructure. Tourism attracts people who can afford to travel. Most of the jobs in the hotels, ports, and restaurants where wealthy tourists visit employ people from poorer communities at low wages. The disparity between the rich tourist and the poor worker creates strong centrifugal cultural dynamics. The gap between the level of affluence and the level of poverty is wide in the Caribbean. In the model of how countries gain wealth, tourism is a mixed-profit situation. Local businesses in the Caribbean do gain income from tourists who spend their money there; however, the big money is in the cruise ship lines and the resort hotels, which are mainly owned by international corporations or the local wealthy elite.

Key Takeaways

- Colonialism created a high level of ethnic, linguistic, and economic diversity in the Caribbean.

The main shifts were the demise of indigenous groups and the introduction of African slaves. - The Caribbean Basin faces many challenges, including natural elements such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and volcanic activity. Economic conditions are often hampered by environmental degradation, corruption, organized crime, or the lack of employment opportunities.

- The Cuban Revolution led by Fidel Castro created a socialist state that nationalized foreign-owned assets and brought about a trade embargo by the United States. Cuba lost its aid from the Soviet Union after the USSR’s collapse in 1991 and has been increasing its focus on tourism and capitalistic reforms.

- Tourism can bring added economic income for an island country, but it also shifts to the service sector resources that are needed for infrastructure and services. A high percentage of tourism income goes to external corporations.

End-of-Chapter Summary

- The Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America make up the realm of Middle America. Two types of development patterns emerged with European colonialism. The rimland, with its plantation agriculture, dominated the Caribbean and coastal regions. The mainland, with its haciendas, dominated Mexico and interior regions of Central America.

- European colonialism decimated the Amerindian population of the Caribbean and conquered the Aztec Empire of the mainland. Colonialism altered the food production, building methods, urbanization, language, and religion of the realm.

- African slave labor became prominent in the Caribbean and altered the ethnic makeup of most islands. Amerindians make up most of the lower working class on the mainland. A minority of wealthy Europeans continue to be at the top of the socioeconomic class structure. Most of Mexico’s population is of mestizo heritage.

- Mexico has transitioned from a Spanish colony to a partner in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Trade relations have helped industrialize Mexico’s economy and provide employment, especially in maquiladoras. Mexico has many natural resources but struggles to provide economic opportunities for its entire population. Wealth and power is controlled by an elite minority with a European heritage.

- Various geographic concepts and principles can be applied to this realm: rural-to-urban shift, core-periphery spatial relationship, altitudinal zonation, and the impact of climate types on human habitation.

- Population growth and the lack of employment opportunities have contributed to the high poverty levels in many areas. There is a wide disparity between the income levels of the wealthy and the poor. Haiti, for example, is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.

- The United States has had a major impact on this region, both politically and economically. The US military has intervened in many places to control its interests. US companies have dominated the region’s economies. Most recently, the United States has supported industrial activities and the implementation of free-trade agreements to take advantage of cheap labor.

- Central America is a diverse and fragmented realm with every country, island, or republic possessing a different geography.

- Tourism is an important economic sector that has mixed impacts on the local situation. Every part of the Middle American realm has sought to improve their tourism draw to help bolster their economy.

- The global economy has prompted the political entities of the region to work more closely together to advance their economic interests. Trade associations such as NAFTA and the Central American-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR) are attempts to develop a greater level of economic integration. Some argue that multinational corporations stand to benefit the most from free-trade agreements.